Authored by:

Robert Koenigsberger, Managing Partner & Chief Investment Officer

Mohamed El-Erian, Senior Advisor

Kathryn Exum, Senior Vice President & Co-Head of Sovereign Research

Petar Atanasov, Senior Vice President & Co-Head of Sovereign Research

May 19, 2020

The CV-19 global emergency has mobilized support for providing debt relief to emerging and frontier markets struggling with the economic and social fallout of the pandemic. So far, debt relief initiatives by multilateral and bilateral creditors have focused on providing liquidity relief in the form of debt forbearance (not debt forgiveness) and budget support to the poorest economies and most vulnerable sovereigns. We believe that in the case of certain sovereigns (some of those who entered the crisis with weak balance sheets, limited fiscal and monetary space, and insufficient external buffers), such efforts may prove insufficient, increasing the probability of them pursuing more comprehensive debt restructurings with private sector involvement.

For many emerging market economies (“EM”), the CV-19 pandemic is truly a “perfect storm” in the form of a triple shock: an unprecedented sudden stop in global economic activity undermining exports, tourism, remittances and foreign direct investment; a sharp drop in commodity prices; and material outflows of portfolio capital. To complicate matters even further, many EM health systems tend to be underfunded and fragile, signaling a weaker capacity to handle the public health emergency. In addition, social safety nets are much weaker and in some cases, non-existent, limiting the effectiveness of EM authorities’ attempts to impose and maintain lockdowns and social distancing policies.

Considering this confluence of risk factors, we believe that a number of EM countries are set to experience severe economic, social and political challenges during and in the aftermath of the current crisis. Navigating the aftermath will require agile policy responses domestically, and will also require more support from the international community.

As far as global capital markets are concerned, the massive stimulus measures deployed by monetary and fiscal authorities in the U.S., Europe, and some parts of Asia – and the commitment to a “whatever it takes” approach – have been an effective financial backstop for markets. They have prevented crippling market failures and an even bigger economic collapse in developed markets (“DM”). The beneficial spillover on EM assets, while notable, has been less dramatic. This disparity is driven by the fact that the largest systemic central banks such as the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) who engaged in unprecedentedly large quantitative easing (QE) programs have not included EM assets in their purchases, while EM monetary authorities have significantly less firepower of their own. Last, but not least, a surge in global demand for U.S. dollars, driven by “flight to quality” by global investors since the CV-19 crisis escalated on a global scale in early March, has starved some EM and frontier economies of foreign currency. This has put significant liquidity pressures on sovereign and corporate issuers with USD-denominated external debt obligations.

With this difficult context for EM, and a grim global economic outlook for the rest of 2020, a number of policymakers from the developing world, mostly in Africa and Asia, have articulated the notion of a debt moratorium for EM until the CV-19 emergency is under control. These arguments are being echoed by some prominent intellectuals and economists in DM, who argue that it is myopic for official and private creditors to expect debt repayments from hard-hit EM economies where the resources would have to be diverted from combating CV-19 and the social and economic damage caused by the pandemic.

While we believe that it will be challenging to execute proactive private sector involvement on a top-down collective and coordinated basis, we also think private creditors need to start getting accustomed to the idea of a materially different economic and political reality in EM in the post CV-19 world and re-underwrite the EM credit universe under that new reality.

So far, the debt forbearance initiatives and other support measures for EM being unveiled by multilateral (IMF, World Bank (“WB”), etc.) and bilateral (G20) creditors have focused on providing short-term liquidity relief and budget support for the most vulnerable countries. Private sector involvement (PSI) is framed as strictly voluntary. However, an implicit “expectation” has been communicated by official sector lenders that private creditors will need to join in the effort for any country that requests assistance. In our view, this creates an important and very complex predicament for national authorities across eligible EM jurisdictions who need to carefully weigh the benefits of short-term debt relief against the potential costs of losing or complicating market access over the medium-term.

In April, the G20 (comprised of 19 systemic nation-states and the EU) announced that its members are prepared to freeze principal and interest payments for the world’s poorest countries (as defined by the WB) through the end of the year and potentially into 2021, subject to economic conditions and the countries’ requests. After the deferral expires, the plan is for the debt service to be repaid over three years with a one year grace period. According to estimates, this effort could free up around $20 billion for the least developed economies to spend on fighting the CV-19 pandemic in the near-term. The debt standstill is open to 76 countries as long as they are current in their debt service payments to the WB and the IMF.

The eligibility for this program is based on the countries’ poverty level and not on the analysis of their respective debt sustainability and/or ability to pay which would have applied in similar relief efforts under normal circumstances and on a case-by-case basis. Among the 76 countries that meet the WB’s poverty guidelines, 39 are in sub-Saharan Africa. G20 bilateral creditors will account for approximately $12bn of the $20bn in liquidity relief that this group is eligible to receive in 2020, while private creditors, whose participation is on voluntary basis, had agreed to roll over or refinance around $8bn, as reported by the press.

On the IMF side, the Fund has been actively looking for ways to fill in some of the gaps in policy support and USD liquidity provision for struggling EM issuers. Its current firepower amounts to around $1tn, but increasing it is subject to political considerations and agreement by the IMF’s main shareholders (i.e. U.S. 16.5%, Japan 6.2%, China 6.1%, Germany 5.3%, France 4%, etc.), which we believe is unlikely in the near-term. The IMF’s outstanding commitments are close to $200bn to over 35 countries, most notably Argentina, Ecuador, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Tunisia, and Ukraine as well as 16 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. This leaves the Fund with around $800bn of maximum available resources, which, given the number of potential EM borrowers that are likely to request assistance and the scale of the crisis, appears relatively limited.

In the current crisis, the IMF facilities that have garnered the most attention of investors are the Rapid Credit Facility (“RCF”) and the larger Rapid Financing Instrument (“RFI”). These instruments, with approximately $20 bn and $80 bn of resources respectively, have already received requests from the majority of the 189 IMF member governments. These facilities are attractive to liquidity-starved EM governments, because they offer much lighter conditionality relative to a full-blown IMF program, which means that disbursement of funds face fewer domestic political obstacles and can be done quickly.

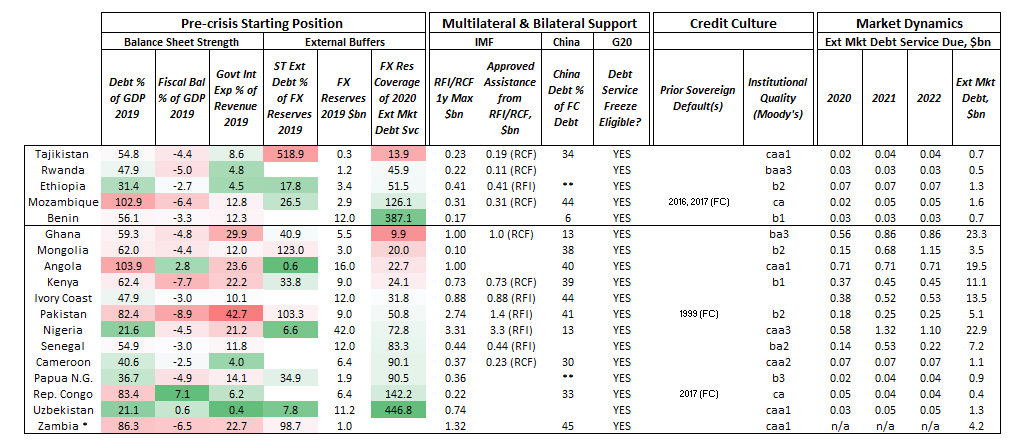

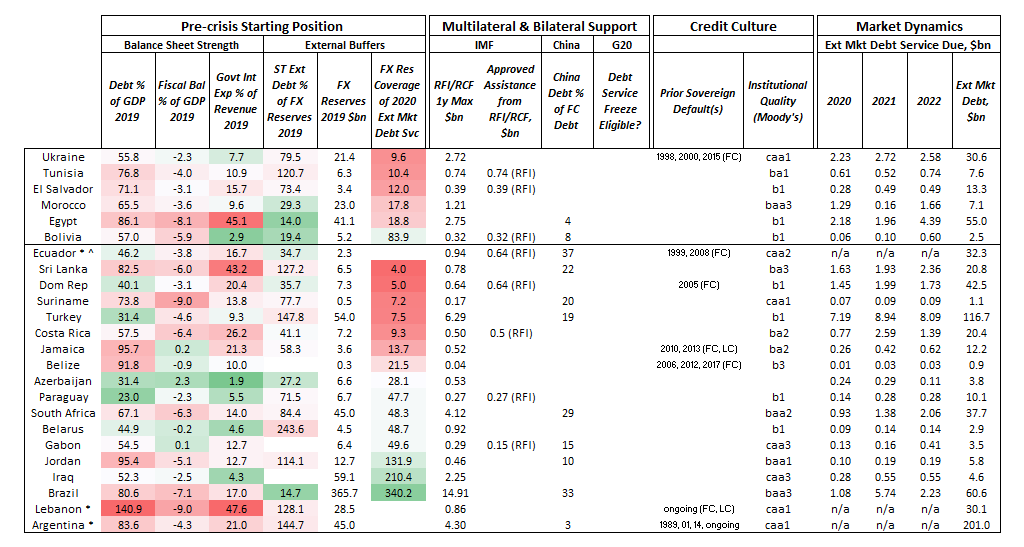

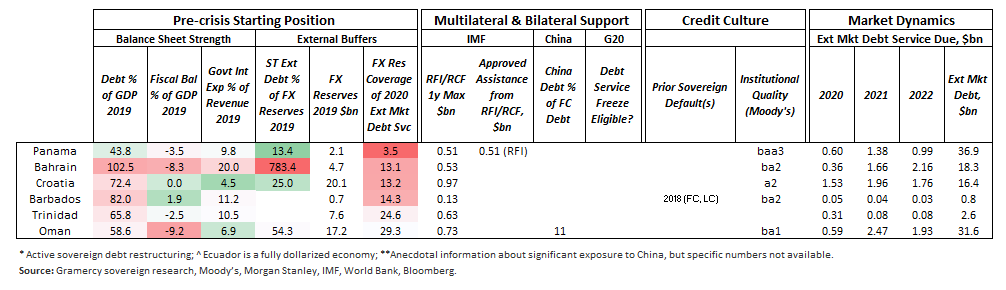

On the flip side, the amounts tend to be small (a maximum of 135% of each country’s quota over first year) and should not be seen as a substitute to a full program. Our summary tables at the end of this report detail the maximum amount of funds that the IMF could disburse to a number of EM sovereigns in 2020 under the RCF/RFI arrangements, the amounts disbursed so far from those facilities, and the market debt service that EM sovereigns face for the rest of this year.

From a bilateral perspective, China’s role as a creditor in EM has surpassed that of the IMF over the past decade with over $300bn estimated to be outstanding to EM economies, the bulk of which is in Africa and Asia. This will be the first wave of sovereign restructurings where China is a key component in many countries, and a potential determinant of debt sustainability going forward.

While China is part of the G20 agreement, the idiosyncratic cases where debt to China is high, debt is unsustainable, and more substantial relief efforts are required, will provide important insights into how China’s restructuring terms and role in negotiations will shape the distressed sovereign’s future growth and earning potential. While new Chinese funds and investments have provided a financial backstop and tailwind for these countries in the past, there may be variation in China’s approach and prioritization of country exposure going forward.

Many of the sovereigns where China has played an outsized role are commodity dependent and revised debt terms that result in pledging of these resources to compensate for cash relief may lower recovery values for bondholders via erosion of the country’s ability, and in some cases willingness, to obtain debt sustainability. While data transparency on this topic is relatively poor, our summary table below provides a snapshot of estimated indebtedness to China for select EM economies.

Liquidity relief and budget support efforts could be insufficient to avert market stress for EM governments with material “pre-existing conditions”.

For EM sovereigns that entered the crisis with weak balance sheets, limited fiscal and monetary space and low external buffers, liquidity relief efforts may have to be complemented by more comprehensive debt restructuring efforts addressing not only liquidity, but in some cases also solvency concerns. Private sector involvement may also be required, especially if multilateral and bilateral creditors take a more material adjustment to their own risk exposures. As such, it is critically important for EM investors to be able to differentiate among sovereign credits based on their underlying fundamental quality in order to avoid making “unrecoverable mistakes” while also taking advantage of the very significant return potential embedded in currently dislocated EM opportunities.

We believe the availability of fiscal space and international reserves to cushion the economic shock caused by CV-19 will be the key credit quality differentiator for EM sovereigns in the foreseeable future.

As a first step, we delineate the EM sovereign universe in two groups. Governments that entered the crisis with prudent fiscal policy frameworks and sizable buffers will have a clear advantage over their peers in terms of ability to absorb the economic and social shocks from the unprecedented sudden stop in economic activity and the likely slow recovery. On the opposite side of the spectrum, the CV-19 shock will crystalize the vulnerabilities of sovereigns with “pre-existing conditions,” especially in the form of stretched public finances and low international reserves relative to their economies’ short-term external obligations. Most governments in this category are in the process of deploying a fiscal stimulus, in some cases quite sizable, given the extraordinary economic and social challenges that they are facing. However, in doing so they will be putting debt sustainability at risk and endangering their market access when conditions normalize.

The most vulnerable among the fiscally weaker sovereigns tend to be the ones that also face external (i.e. balance of payments) pressures such as economy-wide short-term liabilities (due within one year or sooner) that are large in relation of their FX reserves and as such, are subject to material rollover/liquidity risk. Furthermore, some of these sovereigns, especially the ones that are not or have not been engaged with the IMF on a reform program recently, might be facing “broken economic models” that the authorities will need to address in the aftermath of the most acute crisis period. Last but not least, sovereigns with weaker credit profiles from among low and lower-middle income economies (as defined by the World Bank’s methodology) are the ones we think as most likely to take advantage of debt standstills in the current environment.

The global pandemic has prompted unprecedented action by EM policymakers as well as global institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, while official sector creditors are looking into ways to ease the debt burden on the most vulnerable EM economies. However, in the case of sovereign issuers with material “pre-existing conditions” in the form of accumulated fundamental imbalances and weak or non-existing buffers, these efforts may prove insufficient. As such, a careful screening of the EM sovereign universe yields valuable insight as to which credits are most vulnerable to the paradigm of non-payment and where private sector involvement could be necessary, before or after potential default.

Summary framework to examine vulnerability across EM sovereigns.

Low and Lower-Middle Income Economies, Eligible for the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)

Lower-Middle & Upper-Middle Income Economies, Not Eligible for the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)

High Income Economies, Not Eligible for the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)

About Gramercy

Gramercy is a dedicated emerging markets investment manager based in Greenwich, CT with offices in London and Buenos Aires. Our Mission is to positively impact the well-being of our clients, portfolio investments and team members. The firm, founded in 1998, seeks to provide investors with superior risk-adjusted returns through a comprehensive approach to emerging markets supported by a transparent and robust institutional platform. Gramercy offers both alternative and long-only strategies across emerging markets asset classes including capital solutions, private credit, distressed debt, USD and local currency debt, high yield/corporate debt, and special situations. Gramercy is a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC and a Signatory of the Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI). Gramercy Ltd, an affiliate, is registered with the FCA.

Contact Information:

Gramercy Funds Management LLC

20 Dayton Ave

Greenwich, CT 06830

Phone: +1 203 552 1900

www.gramercy.com

Jeffrey D. Sharon, CFP, CIMA

Managing Director, Business Development

+1 203 552 1923

[email protected]

Investor Relations

[email protected]

This document is for informational purposes only, is not intended for public use or distribution and is for the sole use of the recipient. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instruments or any investment interest in any fund or as an official confirmation of any transaction. The information contained herein, including all market prices, data and other information, are not warranted as to completeness or accuracy and are subject to change without notice at the sole and absolute discretion of Gramercy. This material is not intended to provide and should not be relied upon for accounting, tax, legal advice or investment recommendations. Certain statements made in this presentation are forward-looking and are subject to risks and uncertainties. The forward-looking statements made are based on our beliefs, assumptions and expectations of future performance, taking into account information currently available to us. Actual results could differ materially from the forward-looking statements made in this presentation. When we use the words “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “plan,” “will,” “intend” or other similar expressions, we are identifying forward-looking statements. These statements are based on information available to Gramercy as of the date hereof; and Gramercy’s actual results or actions could differ materially from those stated or implied, due to risks and uncertainties associated with its business. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. This presentation is strictly confidential and may not be reproduced or redistributed, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means. © 2020 Gramercy Funds Management LLC. All rights reserved.