Contents

Market Overview

Is the Fed put out-of-the-money? The Fed may well have eased into opportunistic reflation but the lack of additional dovish impulses put markets on the back foot. The narrative is not wholly different from Jackson Hole, yet concrete details were absent. Instead, we can begin mooting average inflation targeting but Powell’s commentary was vague at best. The longer-term view is at least more constructive: 2020 GDP was revised up from -6.5% to -3.7%, with forecasts of 4.0% in 2021, 3.0% in 2022 and 2.5% in 2023, which left us with a median inflation forecast of 2.0% in 2023 and the dots imply that rates aren’t going anywhere for now. Emphasis on Fedspeak is heightened after Kaplan and Kashkari dissented, meaning they will be watched in tandem with Powell’s testimony to the Senate Banking Committee next week. Meanwhile, markets navigated through the chop as Hurricane Sally caused crude to trade higher, in spite of EIA inventory data, OPEC+ and BP not seeing the return in peak demand until next year. Aside from vaccine developments and the resumption in AstraZeneca’s trial, lockdown measures intensified in Israel, Indonesia and the UK, even as South Africa eased to Level 1 (it’s lightest measures yet). The drama around the euro continued, although underplayed by the Fed as the currency pair broke $1.17, reversing the trend to $1.20 and OECD economic revisions weighed little on markets even if the divergence in growth became more stark. Within emerging markets, the EMBI ended the week down 0.3% (4bp wider), where Angola, Kuwait, and Zambia outperformed, while Argentina, Serbia, and Sri Lanka lagged. We note that the Turkish lira made fresh lows as EU tensions cooled over Eastern Med natural resources, where a Summit is now penciled in for September 24-25. This event could even overshadow an important rates decision for Turkey. Other events to focus on will include China’s PBoC rates decision as CNH made 16 month highs against the dollar after posting strong industrial production and retail sales growth. Attention will also be split evenly between rate decisions out of Colombia, Egypt, Mexico, and Nigeria. Beyond that, expect more primary issuance and credit derivatives to roll into new 5yr instruments, which comes as issuer “conference season” peaks with the biannual JP Morgan event.

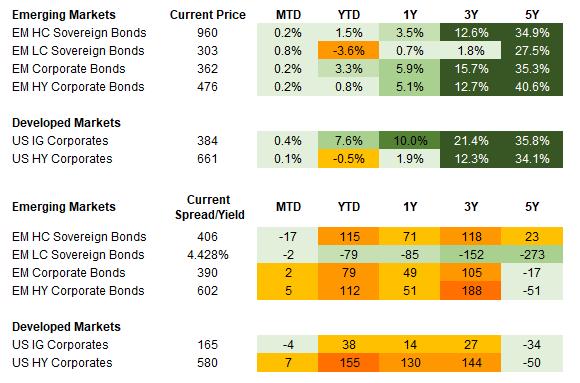

Fixed Income

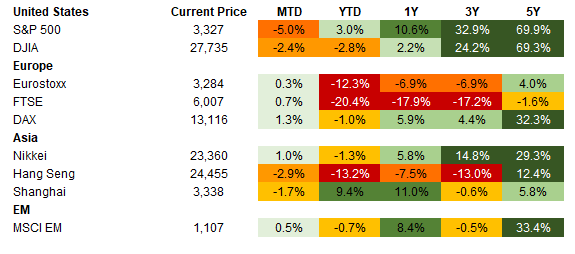

Equities

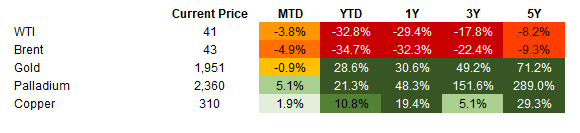

Commodities

Source for data tables: Bloomberg, JPMorgan, Gramercy. EM Fixed Income is represented by the following JPMorgan Indicies: EMBI Global, GBI-EM Global Diversified, CEMBI Broad Diversified and CEMBI Broad High Yield. DM Fixed Income is represented by the JPMorgan JULI Total Return Index and Domestic High Yield Index. Fixed Income data is as of September 17, 2020, Equity and Commodity data is as of September 18, 2020 (Mid Afternoon).

Emerging Markets Weekly Highlights

Argentina tightens capital controls to contain FX reserves depletion, but risks delaying macro normalization; Peru’s latest episode of political drama is a symptom of COVID-induced systemic stress and increases political risks related to the April 2021 general elections; return to lockdowns in Indonesia and Israel highlight continuing challenges for EM from the pandemic and the OECD revises G20 GDP projections, with divergent outcomes for select developing and emerging economies. Finally, we consider the implications of ‘zero for longer’ rates on emerging market corporates.

Argentina tightens capital controls to contain FX reserves depletion, but risks delaying macro normalization

Event: This week, the Fernandez Administration introduced a number of policy measures designed to curtail the outflow of dollars from the economy in order to preserve already scarce FX reserves and alleviate growing pressures on the exchange rate. From a market perspective, the most material new regulation is one that temporarily restricts the ability of local corporates to access dollars for repayment of external debt obligations.

Gramercy commentary: There are a number of important nuances around the most controversial new measure involving restrictions on external debt repayments by private sector companies. The measure applies only to principal payments (interest is excluded) above US$1mm per month and is set to expire in six months (at end of 1Q21). Private sector companies with USD-denominated monthly debt maturities above the $1mm threshold will be allowed to acquire FX at the official exchange rate for up to 40% of the principal coming due. For the remaining 60%, they will face a choice of: a) selling assets abroad (if available) to raise hard currency, b) buy USD domestically at the much higher unofficial exchange rate, or c) negotiate with creditors on restructuring 4Q20 and 1Q21 maturities and present a plan to the authorities by October 1. Beyond the details and the fine print, the policy choice of capital controls tightening that will complicate debt servicing by the private sector is likely to deliver a blow to economic sentiment domestically, while international markets have also reacted poorly. As such, it can be construed as a missed opportunity by the Fernandez Administration to capitalize on the significant positive momentum generated by the recent successful sovereign debt restructuring. At the same time, the authorities’ desire to protect precious FX reserves is understandable, given current low levels of around $40bn of gross reserves and net reserves estimated in a $5-8bn range, of which just $2-2.5bn are liquid (net of gold). In addition, avoiding a large currency devaluation and its feed-through to inflation amidst an intense phase of the pandemic locally is conducive to keeping social tensions relatively low and will buy the authorities some time. This being said, it is very important for Argentina’s credit trajectory that the time bought by controversial policy measures is used wisely to devise a credible and comprehensive strategy to start addressing the fiscal and monetary distortions that are the root causes of capital flight and FX reserves depletion. In fact, the erosion of market confidence we are seeing can be attributed in part to the fact that President Fernandez and Finance Minister Guzman have failed to convince market players that they have a workable plan in mind. In that context, the next six months until the end of 1Q21 will be a crucial period of negotiations with the IMF over a new program, including the rollover of $44bn owed to the Fund from the previous one. We do not think that current episode will derail the upcoming negotiations with the IMF, but the government will need to present a credible plan to the Fund on how it will phase out capital controls and commit to a policy adjustment consistent with fixing the accumulated fiscal, monetary and external imbalances.

Peru’s latest episode of political drama is a symptom of COVID-19 induced systemic stress and increases political risks related to the April 2021 general elections

Event: Political pressures in Peru escalated again this week: President Vizcarra is facing an impeachment investigation by a hostile congress over “moral incapacity”, while his Minister of Finance, Maria Antonieta Alva, survived an attempt by the opposition to oust her over the administration’s economic response to the COVID-19 emergency.

Gramercy commentary: Intense political noise in Peru has been a recurring occurrence in recent months and President Vizcarra, like his Finance Minister, appears likely to survive Congress’ attempt to remove him from office. This being said, the concerning trend from a market perspective is that the significant economic and social fallout from the pandemic is fueling political turmoil even further ahead on an important election in April 2021. As such, public distrust in Peru’s political class is increasing, setting the stage for a highly unpredictable election next year in which populist and non-establishment candidates are likely to be competitive. This is a tendency we expect to see across Latin America and EM in general over the coming years, however, it is especially amplified in Peru at the moment, given the severity of the COVID shock and the looming elections that could have a material impact on economic policy going forward. Peru is among the worst affected countries by the pandemic globally, with one of the highest number of cases and mortality rates per 1mm people. Accordingly, the economy recorded the worst GDP contraction among major EMs in 2Q (-30.2% YoY), notwithstanding the authorities’ allocating an estimated 20% of GDP on COVID-related support measures thus far. Despite a rebound during 3Q, real economic activity is unlikely to return to pre-COVID levels until late 2022. The economic and public health shock and their alleged mismanagement by the administration is what prompted Congress’ attempt to remove Minister Alva. Given Peru’s track record of macroeconomic stability and prudent policy-making and its strong pre-crisis starting position, the sovereign has room to absorb a certain level of credit deterioration stemming from the ongoing multiple crises without material market implications. However, the real test of Peru’s market resiliency will come in the general elections on April 11, 2021. A material structural shift in economic policy toward a more populist approach after the elections is the main factor that could make markets reconsider their structurally positive sentiment on Peru. In our view, at current levels, Peruvian assets price little probability of a populist policy shift. However, episodes of strong political noise are likely to continue boosting the electoral appeal of untested and/or populist political forces ahead of April 2021.

Return to lockdowns in Indonesia and Israel highlight continuing challenges for EM from the pandemic

Event: This week, Israel and Indonesia’s governments reinstituted previously relaxed lockdown measures as confirmed new COVID-19 cases and deaths spiked in early September.

Gramercy commentary: Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital of 11mm people, returned to a partial lockdown this week. All non-essential workers have been asked to work from home, parks, entertainment venues and major mosques will be closed, and restaurants will only be allowed to operate for takeaway dining. Reinstatement of unpopular restrictions was justified by the trajectory of new cases in Jakarta, which, according to the local authorities, suggested that hospitals in the city would likely be overwhelmed in a short period if no immediate action was taken. This is a critically important point in our view, as we believe the risk of overwhelming fragile healthcare systems across EM will determine if governments will be willing to impose a return to highly economically and socially disruptive lockdowns in the event of a material second wave of the virus in the coming months. Such public policy decisions will have a significant impact on market performance, as illustrated by the Jakarta example that sent Indonesia’s assets materially lower. Indonesia’s economy shrank by 5.3% YoY in 2Q, which was relatively good performance in the context of double-digit contractions for most major EM and DM economies in the second quarter. Now, the lockdown threatens to pressure GDP further in 3Q and a continued economic contraction will likely plunge the country into its first recession since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. Similar to Indonesia, Israel also had strict lockdown measures in place in March and April, but has struggled with case growth since relaxing them over the summer. The situation in Israel highlights the key trade-off that EM governments everywhere are trying to manage amid the pandemic: social tensions and economic consequences. In Israel, citizens are feeling lockdown fatigue, as gains from the initial lockdown measures that brought the virus under control were erased in a matter of weeks. In addition, tensions are building within society between the Orthodox population, who have allegedly largely ignored social distancing measures, and the non-Orthodox population as the country is forced to lock down a second time. We expect manifestations of social distress to proliferate across EM in the aftermath of the pandemic, with material economic and political consequences that investors need to take into account in the post-COVID-19 landscape.

OECD revises G20 GDP projections, with divergent directions for select developing and emerging economies

Event: This week, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published their interim economic outlook and latest GDP projections, underscoring that despite lingering high risks and uncertainty, their global outlook is less pessimistic than in June. The OECD upgraded their global growth forecast for 2020 to -4.5% YoY from -6.0% projected in June and projects 5.0% YoY recovery for the global economy in 2021.

Gramercy commentary: We are cautiously optimistic to see the OECD revise its overly bearish global projections from June. However, despite the better outlook globally, we are particularly interested in country level revisions. While the OECD made upward revisions for both China (+4.4pts to positive 1.8% growth in 2020) and the US (+3.5pts to -3.8%), it also adjusted significant lower growth projections for a few important EM economies. The OECD now projects -10.2% YoY growth for India (6.5pts lower vs -3.7% projected in June), -10.2% for Mexico (down 2.7pts from -7.5%), and -11.5% growth for South Africa (down 4pts from -7.5%). The profound economic contractions in some of the largest EM economies this year, accompanied by overall deterioration in fundamentals, will remain a key challenge to their credit resilience as the global economy embarks on the long way toward recovery from the most significant shock since WWII.

Global emerging market corporates in focus: Who moved my yield?

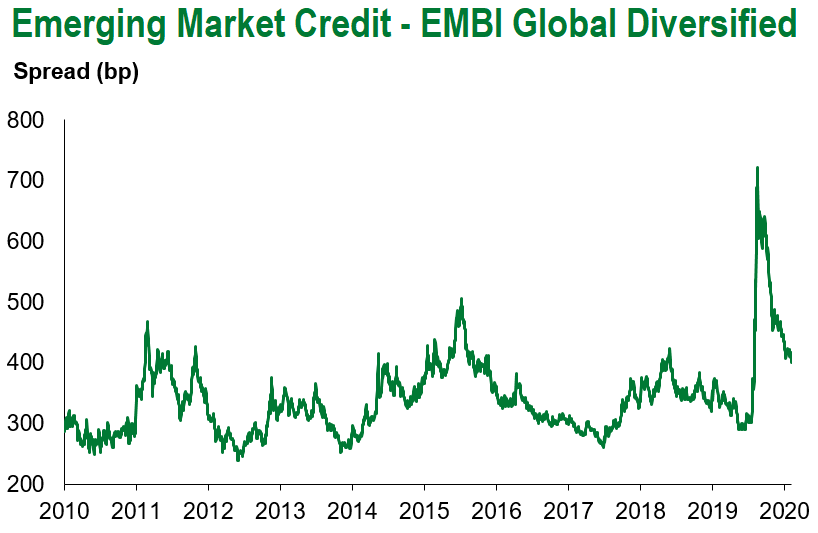

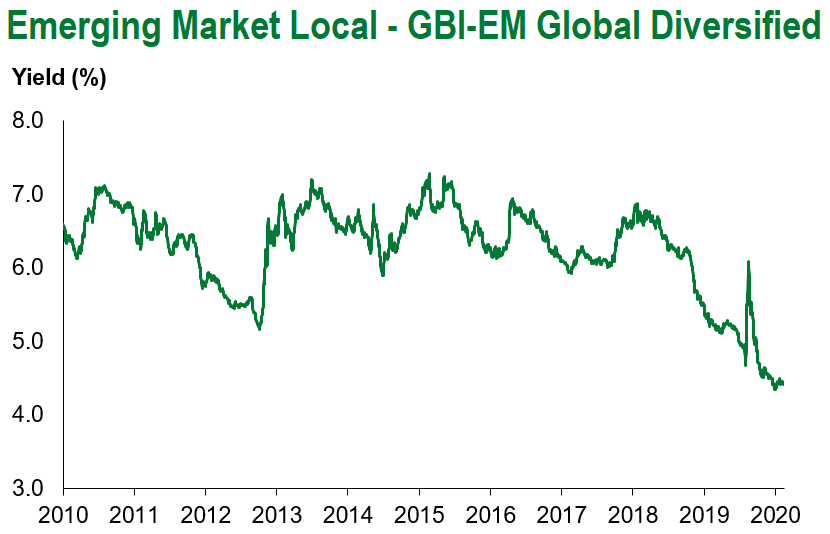

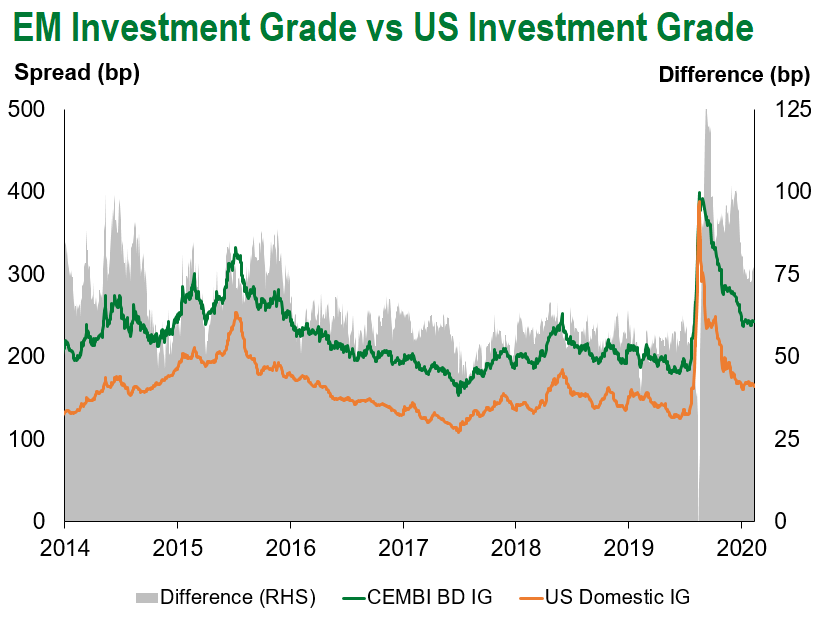

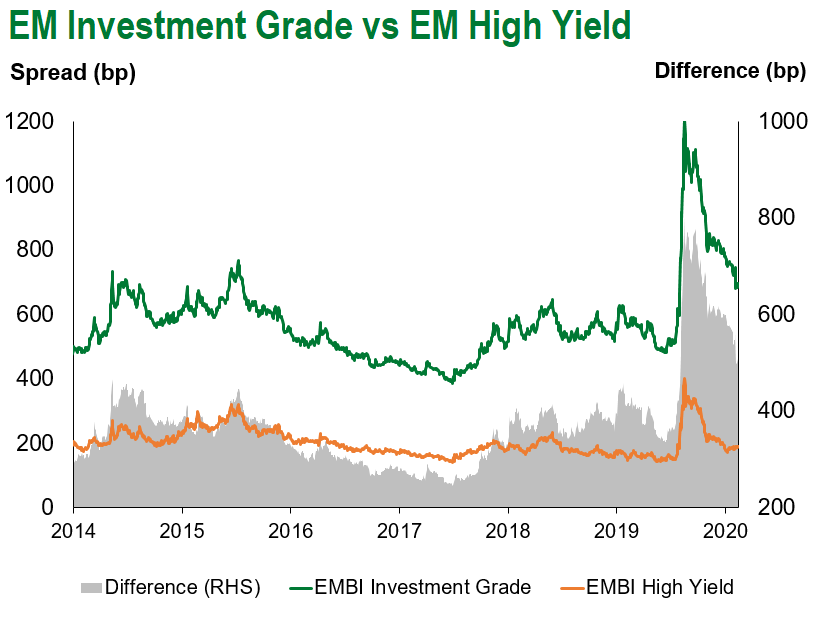

In some ways government stimulus measures put in place to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have helped catalyze the move towards lower rates and lower bond yields in many of our markets. Lower rates mean 5-year, triple-B rated and USD-denominated bonds can yield less than 2%, double-B rated perpetual securities may offer less than 4% to the first call dates in 2025 and some unrated Additional Tier 1 securities can yield even less (under 2% to 2025 call dates). We consider the implications of ‘zero for longer’ rates on emerging market corporates.

One possible consequence may be a rise in merger and acquisition activity. There may be two reasons for this – lackluster economic growth and more attractive debt market funding. With many emerging market economies still expected to shrink this year and with 2021 growth forecasts under threat in some jurisdictions, issuers may consider accretive inorganic opportunities as they seek to improve shareholder returns. In addition, bond market pricing available to some issuers – especially investment grade corporates – may mean that acquisition opportunities previously dismissed on financing grounds may now make better sense.

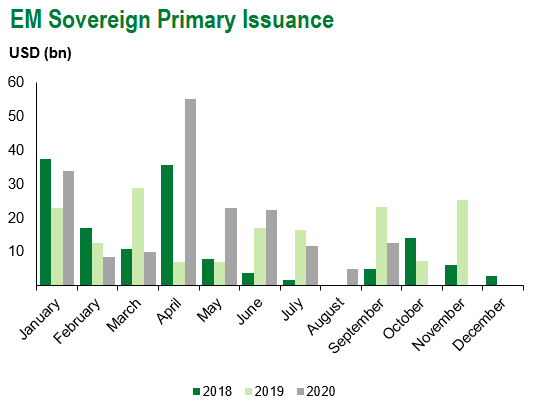

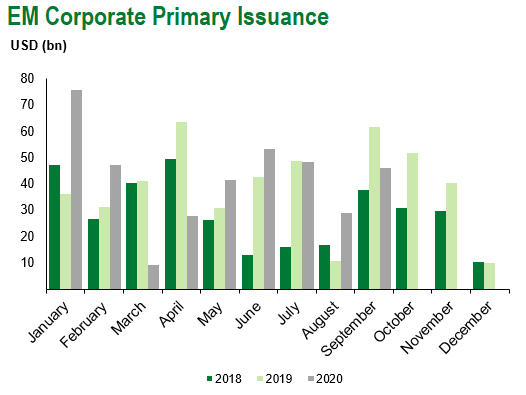

There may be an increase in issuance unrelated to acquisition activity. We discussed this in a previous EM Weekly. For some issuers, funding costs in both foreign and domestic markets are at unprecedented lows, making pre-funding of future needs more of a consideration. Related to this, we are already seeing issuers carrying out liability management exercises where existing, higher coupon securities may be replaced with new, lower coupon bonds or with cheaper funding from sources other than the Eurobond market. This is expected to continue. Such buybacks have been positive for existing bonds, with corporates typically offering above-market prices to convince holders to tender their securities. Some issuers may seek longer-term funding than they would ordinarily. The duration of the asset class may change if this becomes a trend.

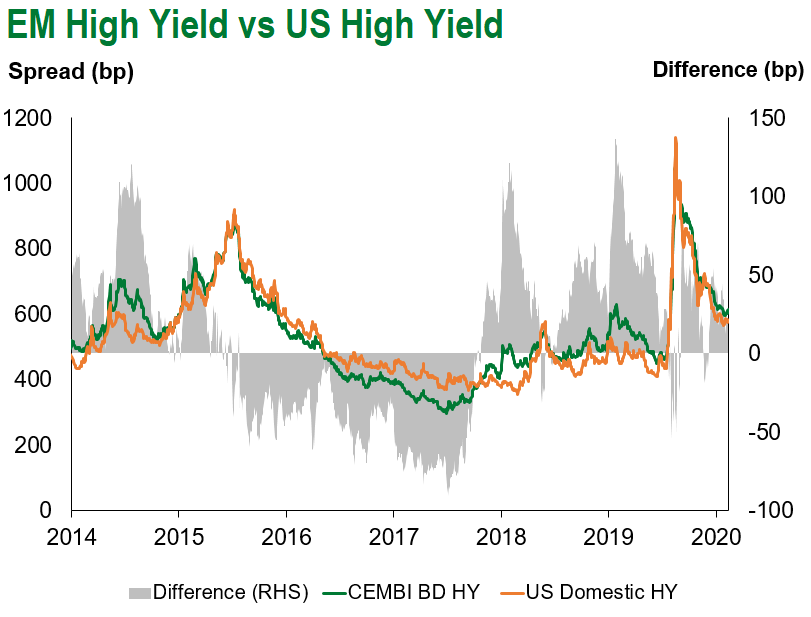

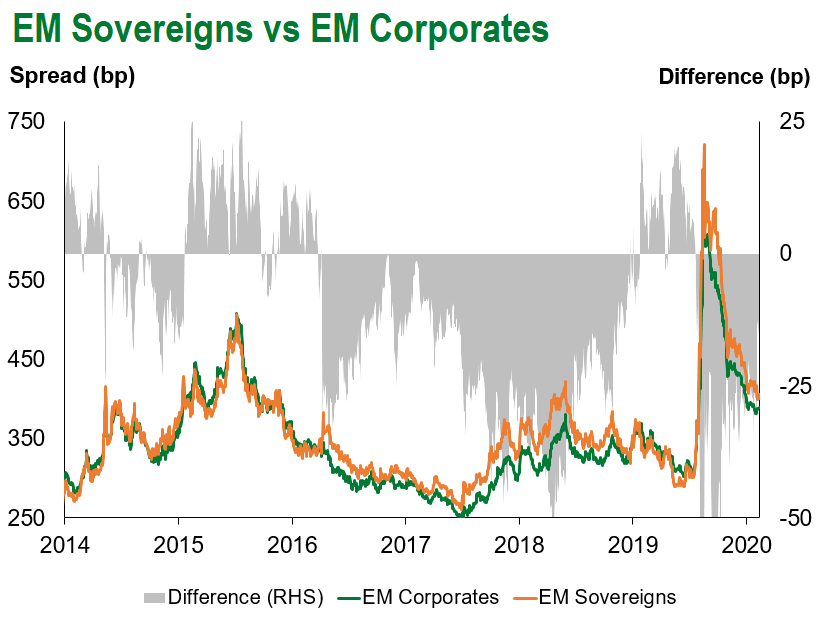

In the search for yield, there may be increased demand for emerging market bonds, which can sometimes offer better value than similarly-rated developed market peers, particularly in Latin America and in Central and Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa (CEEMEA). These inflows, when sticky, can be positive for emerging markets.

For lenders, lower deposit and other funding costs are positive for margins. However, at least some of this may be passed on to borrowers as loans are refinanced, offsetting that positive margin impact. In addition, government-linked schemes in some countries have resulted in lower loan yields in some countries, leading to margin pressure. The overall impact of lower rates at some banks could actually be narrower loan-deposit spreads. Other income sources such as fees and trading may become even more important for banks. For non-financial corporates, lower funding costs can help offset the effects of the pandemic on volumes and revenues.

There are caveats to all of this. Our markets are not devoid of defaults. This is in part because lower rates are not necessarily available to all issuers. Other issuers have repaid maturing bonds, exiting the Eurobond market. Some have found more cost effective funding in other markets. In addition, there are questions about how low coupons can get in the USD emerging market corporate bond market. Could we see emerging market corporates effectively paid to issue soon? We’ll have to wait and see.

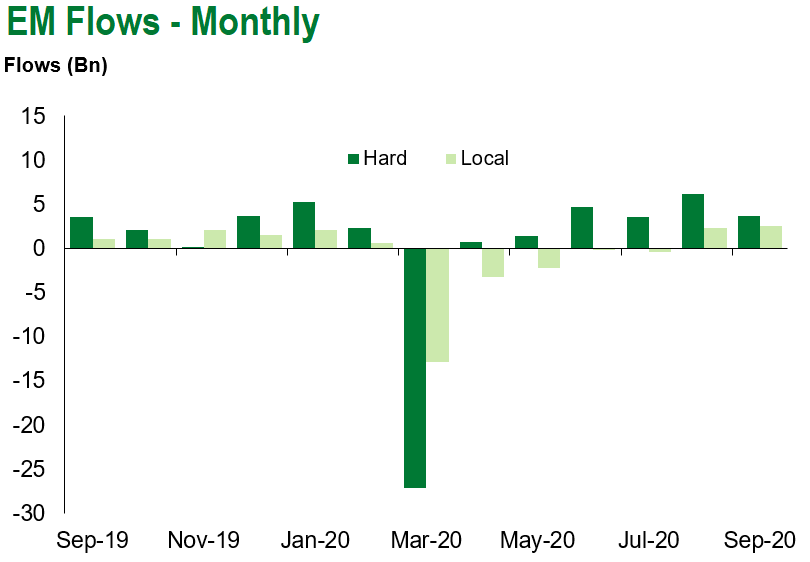

Emerging Markets Technicals

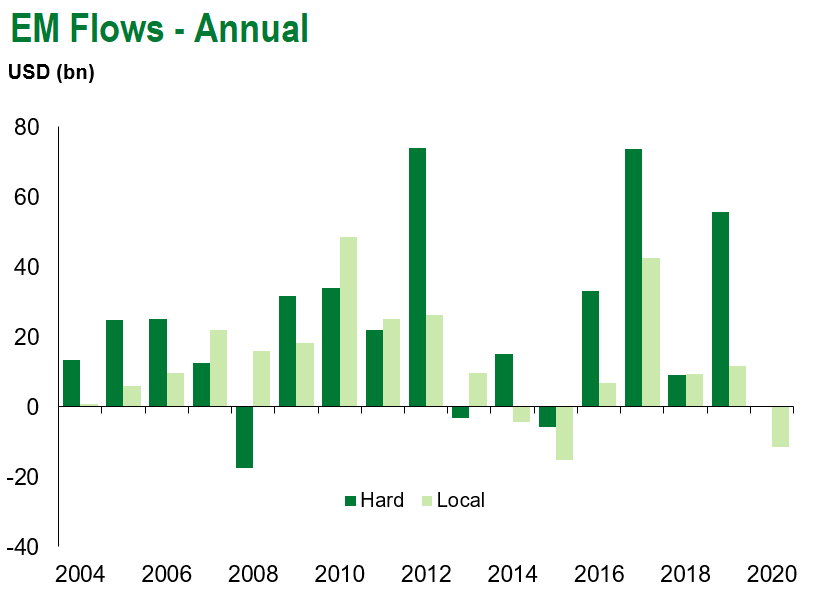

Emerging Markets Flows

Source for graphs: Bloomberg, JPMorgan, Gramercy. As of September 18, 2020.

COVID Resources

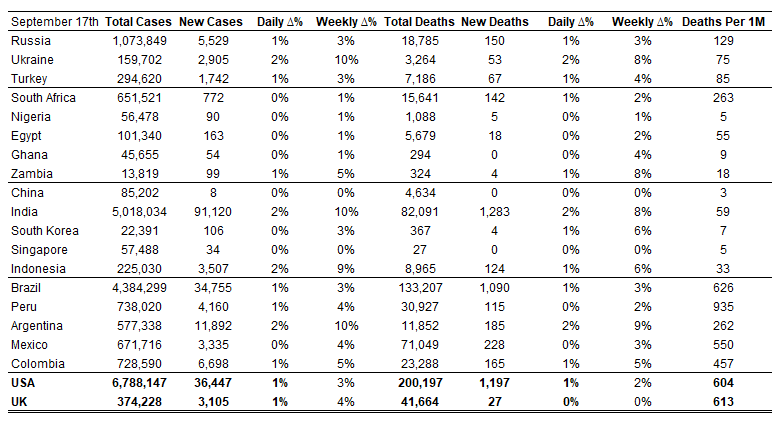

Emerging Markets COVID-19 Case Summary

Source: Worldometer as of September 18, 2020.

Additional Crisis Resources:

Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Case Tracker

For questions, please contact:

Kathryn Exum, Senior Vice President, Sovereign Research Analyst, [email protected]

Petar Atanasov, Senior Vice President, Sovereign Research Analyst, [email protected]

Tolu Alamutu, Senior Vice President, Corporate Research Analyst, [email protected]

James Barry, Vice President, Corporate Research Analyst, [email protected]

This document is for informational purposes only. The information presented is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. Gramercy may have current investment positions in the securities or sovereigns mentioned above. The information and opinions contained in this paper are as of the date of initial publication, derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed by Gramercy to be reliable, are not necessarily all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. This paper may contain “forward-looking” information that is not purely historical in nature. Such information may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this paper is at the sole discretion of the reader. You should not rely on this presentation as the basis upon which to make an investment decision. Investment involves risk. There can be no assurance that investment objectives will be achieved. Investors must be prepared to bear the risk of a total loss of their investment. These risks are often heightened for investments in emerging/developing markets or smaller capital markets. International investing involves risks, including risks related to foreign currency, limited liquidity, less government regulation, and the possibility of substantial volatility due to adverse political, economic or other developments. The information provided herein is neither tax nor legal advice. Investors should speak to their tax professional for specific information regarding their tax situation.